Last Friday evening, Darrin Reay left his home in southwest Colorado to meet friends at a remote camping spot he loved surrounded by sandstone cliffs in the desert beyond Moab, Utah.

When he arrived, he was alarmed to hear the suggestion of climbing a bolted route. Reay knew of no drilling on this certain slab, no anchors to hold climbers’ clips. And that was for the good of ancient art on the rock above, left by Indigenous people more than 1,000 years ago.

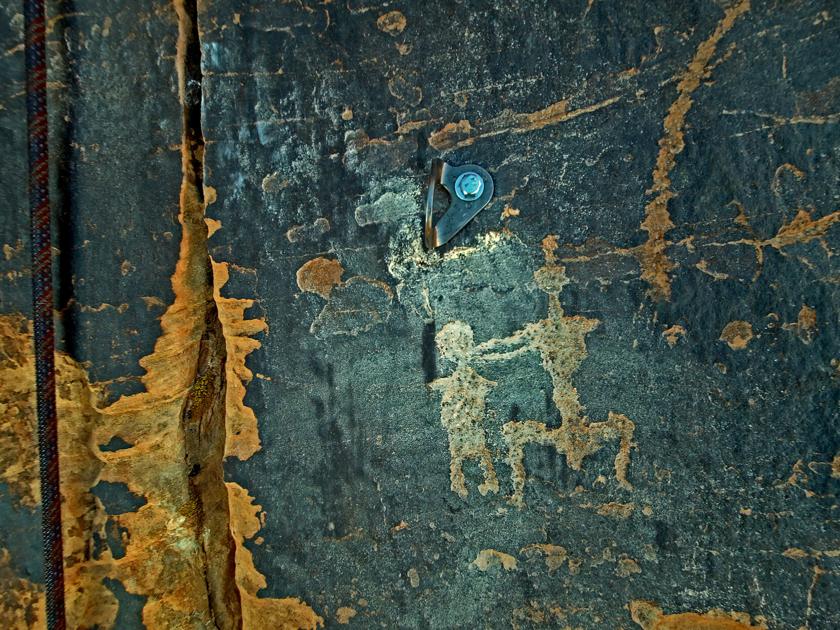

“I started climbing,” Reay recalled, “and I look up, and all of a sudden I’m standing before a giant petroglyph with a line of bolts going right through the middle of it.”

He was “horrified and angry.” He called his old mentor, Stewart Green, the Colorado Springs-based writer and historian who is something of an authority in American climbing, an advocate born from the sport’s 1970s emersion in the West.

Green couldn’t believe it. “What the hell?” he remarked.

Thus sparked an online storm of outrage that swirled with fears of lost privileges for climbers in the legendary desert, where long before them Ancestral Puebloans and Fremont people left their marks — sacred places for descendants today, reminders of the culture that came first in the region.

Bolts have since been removed from the outcrop known as Sunshine Wall north of Arches National Park. But damage to the petroglyphs is forever, said Elizabeth Hora, archaeologist for the Utah State Historic Preservation Office.

Hora called damage “shockingly common” around the state.

A bolted climbing route along petroglyphs on rock outside of Moab, believed to be left by Indigenous people more than 1,000 years ago. Photo by Darrin Reay

“And it’s heartbreaking, and it’s a little different every year,” she said. “People are very creative in the way they damage things, which just means we don’t have a very good understanding of what it is driving behaviors.

“But we firmly believe here in our office that shaming and blaming is not the way to make change.”

She considered herself and colleagues “horrified” by what they read across social media: comments threatening to kill the perpetrator.

Richard Gilbert, 36, of Colorado Springs has confessed guilt. Along with death threats, he told The Gazette someone proposed his hands be cut off.

“I deserve it,” he said of the scorn. “I’ll take it.”

Late last month, Gilbert said, he posted a description of his bolted route that he called Peaches, rated a gentle 5.3. This description came with his mention of “graffiti.”

Upon reading comments to the post, Gilbert said he became convinced late Sunday that he mistook the images. Soon after, he said, he left the Springs to report to a ranger at Moab’s Bureau of Land Management field office.

A bolted climbing route along petroglyphs on rock outside Moab, believed to be left by Indigenous people more than 1,000 years ago.

Under the Archaeological Resources Protection Act, first-time violators could be fined up to $20,000 and imprisoned for up to one year.

In a statement to The Gazette on Thursday, the BLM declined to provide details “as the placement of the climbing bolts is an active, ongoing investigation.” The statement added: “We ask the public to let the appropriate authorities determine next steps. The BLM does not endorse harassment or threatening behavior.”

On Thursday, Gilbert said he had yet to hear from authorities. He said he was getting rid of his outdoor gear.

“Kinda crazy,” he said. “You’re out there making some routes for some disabled guys and young kids, and then you’re sitting in prison.”

Gilbert said he was medically retired from the military and had been climbing since 2006, traveling to crags around the country after becoming inspired through Wounded Warrior Project.

In recent years, he had been bolting routes “so that there’s better access for people not just with disabilities,” he said, “but also for people learning to climb.” While not illegal on all public land, bolting for the sake of low-grade routes is frowned upon in climbing circles.

“Mistakes are made, and that doesn’t make it any better I know,” Gilbert said. “It’s not. I made a mistake.”

They’re happening more in Utah’s archaeologically-rich landscape, Hora said. She said there was “an explosion” in 2020, the pandemic year marked by unprecedented outdoor crowds, which coincided with reports of spray paint and degradation also to sensitive geology around the Pikes Peak region.

Malicious intent was rare in Utah’s famed canyonlands and deserts, Hora said.

“We make mistakes,” she said. “And to be totally honest, my hands are not clean in this either. As an archaeologist here and someone who loves the outdoors and does care about archaeology and prehistoric rock art, I see I’m the one who didn’t equip people with the information and knowledge to make good choices.”

That’s the goal of the new, multi-agency Stop Archaeology Vandalism initiative.

And it should be the goal among climbers, Green said.

“Especially now with the increased number of use, we really need to adopt a Leave No Trace ethic,” he said. “A lot of people nowadays are coming out of gyms, and they’re having a lot of fun and not really thinking about all we have to do to be a responsible user group.”

In a joint statement condemning the bolts at Sunshine Wall, some of the nation’s lead climbing organizations called archaeological education “essential,” saying “the cultural and spiritual value of these places cannot be measured.”

Land managers have closed climbing areas for past infractions. Reay worried this one would represent another crack at the sport’s existential core.

“The history of rock climbing is someone did something crazy no one else had done before and risked their life doing it. I don’t want us to have to ask for permission to do that,” he said. “But at the same time, if people can’t do it responsibly, we’re gonna be regulated and not allowed to do it again.”

Born and raised on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming, Reay considered Gilbert’s act “sacrilegious.” Reay called it “arrogant and ignorant.”

“My main reason for sharing the story is to try to educate other climbers and the public not to repeat these mistakes,” Reay said.

Gilbert said that was his aim, too. He said he has connected with advocacy groups to help spread the message.

“There’s no reason for this to have ever happened,” he said, “and it definitely never needs to happen again.”

This content was originally published here.