To prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt is a fundamental, easily recognizable principle of the criminal justice system. Judges recite the legal definition of reasonable doubt over and over again to ordinary citizens called to sit on juries.

Less clear is whether judges ought to describe in simpler terms what the concept means for jurors — so much so that the state’s highest court is now weighing whether plain-English explanations are so problematic they undermine a defendant’s right to a fair trial.

In two cases pending before the Colorado Supreme Court, the justices must decide if judges’ well-meaning illustrations of reasonable doubt effectively lowered the burden of proof beyond what the Constitution allows, and if that warrants tossing both convictions.

Reasonable doubt illustrations frequently take the form of analogies to everyday situations. One Adams County judge invoked a jigsaw puzzle with pieces missing when talking to the jury.

“When you get to the bottom of the box you find that, by golly, you didn’t get all the pieces,” the judge said, adding, “You might be able to figure out that there’s a barn and a corral and a house there, even if you can’t see it all. That might be enough proof beyond a reasonable doubt based upon your interpretation of what it is you see and what you don’t.”

Time and time again, the state’s second-highest court has politely chided judges for such voluntary illustrations of reasonable doubt. In fact, appellate judges have, since August 2010, reviewed roughly 30 cases where trial courts attempted to clarify, sometimes clumsily, the concept of reasonable doubt for incoming jurors.

For the most part, the Court of Appeals let the judges’ decisions stand.

But last month, two cases calling into question judges’ illustrations of reasonable doubt landed at the state Supreme Court. One member spelled out the stakes behind the cases: If a handful of trial judges keep thumbing their noses at the appellate court, it may be time for the high court to put its foot down.

“It seems like the only way to get the attention of the trial courts is to reverse one of these, right?” said Justice William W. Hood III. “We typically say it, but do we really mean it?”

Defendants argue that comparing the act of convicting a human being of a crime to mundane activities, such as completing a jigsaw puzzle, undermines the high burden of proof that prosecutors need.

“All that a court is supposed to do is read those instructions and those definitions at the beginning of jury selection and then furnish them in writing to the jury before they begin deliberation,” criminal defense attorney Ann Roan said. “The problem is that when judges or prosecutors or defense lawyers try to restate fundamental constitutional principles, unless they are very, very careful, they end up misrepresenting the fundamental underpinnings of our criminal system.”

By contrast, Heidi McCollum, the district attorney for the 5th Judicial District in Summit, Eagle, Clear Creek and Lake counties, said the propriety of the tactic depends on who uses the reasonable-doubt illustration, what analogy is employed and how it is delivered. McCollum has no fundamental problem with such illustrations. In fact, she welcomes some guidance from judges.

“To just give a jury a definition of what reasonable doubt is and say, ‘Well, now you’re on your own’ — I don’t think that’s fair to the jury, quite frankly,” she said.

Add ‘flesh to the bones’?

Reasonable doubt analogies tend to center on tangible items or concepts: Buying a used car while understanding there may be things wrong with it, knowing someone’s birth date despite the possibility the birth certificate is wrong, identifying an American flag even though it is partially obscured.

The message in those examples is that while some doubt is inherent in lots of things, all that matters to a juror is whether the doubt is reasonable.

When a judge — who gives the jury its instructions — uses such an illustration, the legal question revolves around whether he or she is actually giving people the impression during jury selection that “beyond a reasonable doubt” is less rigorous than the law envisions. One Court of Appeals judge, Ted C. Tow III, described succinctly the paradox of trial judges attempting to eliminate confusion for juries with plain-English explanations.

“Well-intentioned trial courts, seeking to provide additional clarity to prospective jurors, sometimes feel the urge to go beyond these instructions and either insert their own supplemental instructions or attempt to add ‘flesh to the bones’ of the standard instructions by providing examples and hypotheticals,” Tow wrote in 2019.

The problem, he said, is that an inarticulate attempt to do so “may result in automatic reversal, deviating from or expounding on the standard instructions in this area is undeniably risky, in that it exposes the conviction to a challenge that the comments lowered the burden of proof.”

In Colorado, the criminal jury instructions define reasonable doubt as a doubt “based on reason and common sense” that arises from a rational consideration of the evidence in a case. It is not vague or imaginary, but rather something that “would cause reasonable people to hesitate to act in matters of importance to themselves,” the instructions read.

The U.S. Supreme Court first offered a reasonable-doubt instruction in 1827. An early definition that became widespread included an element of “moral certainty” but was displaced with the “hesitate to act” standard.

Using analogies and other illustrations to demystify the concept of legal doubt for juries is by no means limited to Colorado. The Hartford Courant in 1994 reported that one Connecticut judge described reasonable doubt as going “past the 50-yard line, but not all the way to the end zone.” A Nevada judge said reasonable doubt was “about 7½” on a scale of 1 to 10.

And wherever trial judges use such analogies, appellate courts reprimand them.

“We are not prepared to say that people planning vacations or scheduling flights engage in a deliberative process to the depth required of jurors,” the 2nd District Court of Appeals in California observed drily in 2004 after a Los Angeles County judge compared reasonable doubt to both vacations and flights.

Similarly, when a Manhattan judge likened reasonable doubt to being able to identify Abraham Lincoln in a jigsaw puzzle without having all the pieces, a New York appellate court retorted in 1988 that the average American would recognize Lincoln “long before” completing the puzzle.

That, the court maintained, is not how reasonable doubt operates.

A question of clarity

In Colorado, the state Supreme Court ruled on the subject as recently as two years ago. A jury convicted Crystal Johnson of narcotics possession in Mesa County. But on appeal, the justices could not make heads or tails of District Court Judge Thomas M. Deister’s attempt to clear up the concept of “hesitating to act” during jury selection.

Deister said jurors should find Johnson not guilty “only if, after hearing all of that evidence, you just can’t bring yourself to do it. You just have to hesitate. It’s not there. You can’t find her guilty because the quality or quantity of evidence just doesn’t let you.”

The Court of Appeals declined to reverse Johnson’s conviction, because it had no idea what Deister was talking about. The Supreme Court agreed that the judge had not lowered the burden of proof, because he had not communicated a clearly formed statement about the burden of proof at all.

“That language is indecipherable,” now-Chief Justice Brian D. Boatright wrote. “Even with the benefit of a transcript and the luxury that time gives us to parse every word, it remains unintelligible. Therefore, because the problematic portion of the ‘hesitate to act’ instruction is unintelligible, we cannot presume that the jury understood it.”

In the absence of further Supreme Court directives, the Court of Appeals’ message to judges is unequivocal: Avoid reasonable-doubt illustrations.

“In Colorado and elsewhere, courts have repeatedly discouraged the practice of analogizing reasonable doubt to pretty much anything,” wrote Judge Jerry N. Jones in 2018.

The Court of Appeals, however, has largely manifested its frustration through words and not action. In nearly every instance, the court has declined to reverse a conviction based on a judge’s illustration of reasonable doubt.

Some trial judges have noticed the Court of Appeals’ repeated weigh-ins on the issue and taken heed.

“There are enough reversals among those opinions that I just stay away from that minefield,” said Chief Judge William Bain of the 4th Judicial District, which covers El Paso and Teller counties. He added that he does not use reasonable doubt illustrations during jury selection.

A shift on the court

Only a handful of dissenting appellate judges have actually viewed a judge’s reasonable doubt comments as serious enough to reverse a conviction.

That began to change in 2019, when Judge Neeti Vasant Pawar joined the Court of Appeals. An appointee of Gov. Jared Polis, Pawar ran her own law firm before joining the bench and practiced criminal defense. Shortly after graduating from law school, she worked in the Denver municipal public defender’s office.

Six months after her appointment, Pawar sat on a three-judge panel hearing the appeal of Ernest Joseph Tibbels in which the trial court judge, Robert W. Kiesnowski Jr. of Adams County, attempted to illustrate reasonable doubt through a common analogy: A crack in the foundation of a house.

“So you and your spouse and your children are in a market to (buy) a house,” Kiesnowski began. “And you come upon that ranch and it’s just like the dream come true, okay. The price is right. Interest rates are still good.”

The house, however, had a crack in the foundation, he went on. “And it’s not that superficial cracking that concrete will do. And structurally it’s significant. Are you going to buy that house?”

A juror answered no. Kiesnowski later reminded the jury, “It’s that example that I gave you — what a reasonable doubt is.”

During oral arguments in the appeal, Daniel M. Taubman, the longest-serving judge on the appellate panel, said that, to his recollection, there was a long string of Court of Appeals decisions that kept convictions intact under similar analogies.

“I believe you are correct, unfortunately,” the public defender answered.

When the panel announced its 2-1 decision, Pawar found herself in the minority. Her reasoning contrasted with the Supreme Court’s opinion in the Johnson case. Whereas the judge’s instruction there was unintelligible, Kiesnowski’s analogy had the opposite effect: It was so concrete that jurors would logically gravitate to the example.

“I think it far more likely that the jury took note of and remembered the only time the court explained, in familiar and accessible terms, what constitutes reasonable doubt,” Pawar wrote.

Less than two months later, Pawar’s minority view — that a structural error occurred requiring reversal of the conviction — became the majority opinion.

Another Court of Appeals decision had come out, this time ordering a new trial based on a judge’s comments. In another case from Adams County, Judge Thomas R. Ensor told the jury that beyond a reasonable doubt is a standard for “when we do important things in our lives, like buying a home, or choosing doctors, or whatever.”

He then asked whether a juror could hold the prosecution to that burden “and not require them to prove anything more.”

The resulting 2-1 decision in People v. Knobee rejected the idea that taking away a defendant’s liberty is the same as choosing doctors “or whatever.” This time, Judge Diana Terry, joined by Pawar, determined Ensor’s analogy, coupled with his extraction of a commitment from the juror, made this case different from all the others, in which the appellate judges upheld the trial courts’ decisions.

The momentum continued. In yet another appeal out of Adams County, People v. White, a 2-1 panel found the judge flipped the burden of proof on its head when illustrating reasonable doubt by ticking through a list of defects in a home, each one contributing to more doubt that a homebuyer should continue with the purchase.

“This is backward,” read the majority decision on Nov. 4 of this year, adding the jury should “start with all the doubt in the world about the defendant’s guilt.”

The opinion’s author was Neeti Vasant Pawar.

‘He did something’

It is not a coincidence that the Tibbels, Knobee and White cases all arose from Adams County. Of at least 34 Court of Appeals cases since 2001 — most of them occurring in the past decade — 79% of them originated in Adams County.

Chief Judge Don Quick declined to speculate on why his jurisdiction is the outlier.

“In the nearly seven years I have been on the bench, I am not aware of anyone encouraging judges to use examples or illustrations to explain the term ‘reasonable doubt,'” said Quick, whose own use of a reasonable-doubt analogy the Court of Appeals upheld in 2019.

The time and energy spent reviewing these cases from Adams County emanated from the work of two men: Ensor and Francis C. Wasserman. Although now retired, they served as the trial judges in roughly half of the appeals from Adams County.

Ensor’s work is no stranger to the state’s appellate courts. In March of this year, a Court of Appeals panel ordered a new trial after Ensor humiliated the defendant’s lawyer so severely that, the appellate court concluded, he compromised the right to a fair trial.

Last year, another panel tossed a conviction because Ensor failed to read the entirety of a jury instruction. And while a majority of the state Supreme Court found it permissible that Ensor allowed his wife to serve on a jury while he sat as the trial judge, the court wished he had “handled this unusual situation in a more restrained manner.”

Ensor typically elaborated on reasonable doubt using a folksy recitation of occasions in which jurors, he said, use their judgment to evaluate probability and risk.

“Anything can happen on any given day. We can have an earthquake here in Brighton, Colorado. … Whoever would have thought that somebody would land a jet airliner in the middle of the Hudson River and nobody dies? Crazy, crazy story, but it happened,” Ensor said during a jury selection.

He continued: “But I’ll bet you when you drove up here — or when you came up here, that you drove, and when you drove your car up to Brighton, Colorado, you didn’t hesitate and pause in front of your car and say, ‘Gee, should I take that chance one more time?’ What you did was you used reason and prudence and common sense and your experience as an adult.

“You didn’t go 100 miles an hour, you didn’t start drinking at 4 this morning, and you got here safely. And if you use reason and prudence and common sense and your experience as an adult, you’re going to get home safely tonight.”

For his comments, Ensor earned this response from the Court of Appeals: “We do not think that people customarily make private decisions according to this (reasonable-doubt) standard, nor may it even be possible to do so.”

After one defendant pointed out that Ensor had previously been warned about his style, the Court of Appeals defended him by saying, “We do not know that the judge was aware” of the previous admonition.

Wasserman became a judge in 2005, one year after ABC News featured a trial he prosecuted on its “In the Jury Room” documentary series. After the broadcast, he reportedly received an invitation to lecture on American jury trials at the University of Iceland and speak about the criminal justice system in Belgium.

Wasserman’s spiel about reasonable doubt included this monologue about the defendant.

“Let me tell you something, folks. (The defendant) did something. I’ll tell you that much right now. He did something. All right?” Wasserman said. “We didn’t just go out on the street in the front of the courthouse this morning and say, ‘Hello … it’s your lucky day.’ OK? Of course, he did something.”

Although he also employed more conventional illustrations of reasonable doubt — cracks in a building, a birth date, etc. — it was Wasserman’s insistence to jurors that the defendants “did something” that the appeals court warned against.

“The better practice would have been to avoid a suggestion that defendant ‘did something,'” wrote Chief Judge Janice B. Davidson in January 2012.

Two months later, she penned another opinion about Wasserman’s comments in a separate case, observing that Wasserman was “apparently” telling juries that defendants had done something “as a matter of course.”

Wasserman told Colorado Politics that he did not agree with the appellate court’s opinions, but he “softened” his views after seeing the repeated admonitions.

“I decided it’s not worth allowing for this to be an issue,” he said. Wasserman added that he had high regard for jurors, and when he told them the defendant had done “something,” it was to counter an impression that the defendant had done “something wrong.”

“Defense attorneys knew how I conducted my voir dire,” he said. “They knew what I was doing and never objected.”

Supreme Court to weigh in again

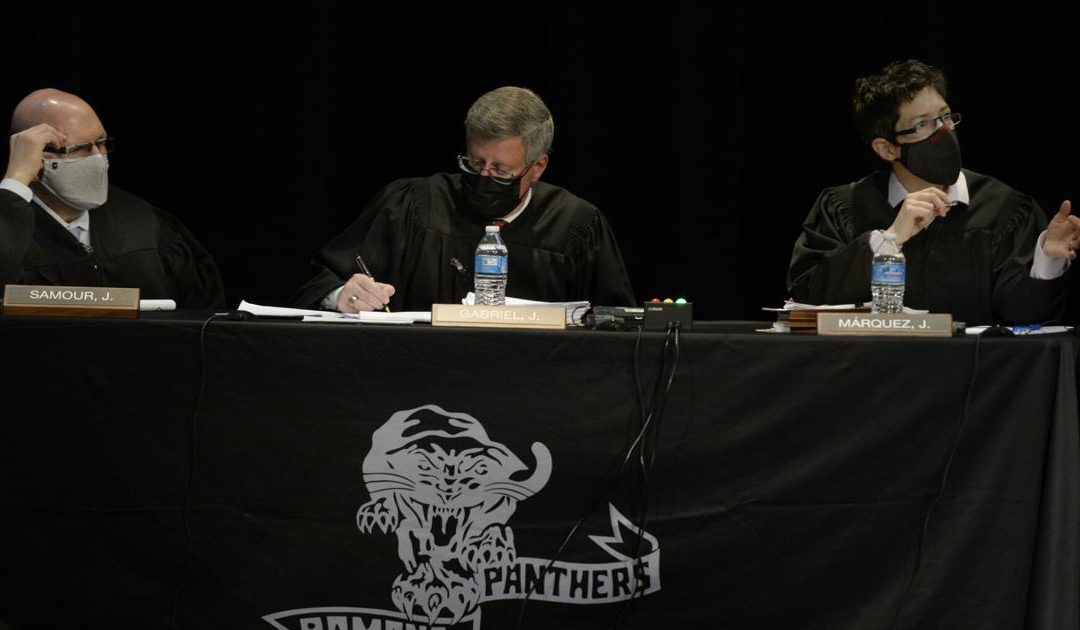

When the state’s Supreme Court justices confronted the issue of reasonable doubt analogies in October, the sheer volume of questions became apparent. When does a judge go too far? Is any analogy appropriate? Does an illustration risk giving a different frame of reference to each juror?

Then, Justice Carlos A. Samour Jr., who is himself a former trial judge, wondered if the reasonable-doubt analogies themselves are not the real problem.

“Do we need a different definition? I know when I read that definition, jurors used to look at me like, ‘What? What does that mean?'”

The current definition of reasonable doubt — the one involving hesitation to act in matters of importance — is not gospel. The late U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg once pointed to a different wording she preferred, instructing jurors to be “firmly convinced of the defendant’s guilt” or else “think there is a real possibility that he is not guilty.”

In one of the appeals the Colorado Supreme Court heard, that of Ernest Joseph Tibbels, where the judge used a crack-in-the-foundation analogy, the public defender asked the justices to bar the use of judges’ reasonable-doubt illustrations entirely.

The attorney general’s office, by contrast, rejected such a “hyper sensitive” reading of the judge’s comments.

To some, it is incredulous that the justice system relies on a concept that becomes more problematic when judges attempt to explain it. But to Wasserman, it would be even more incredulous for the Supreme Court to reverse a conviction to send a message about analogies.

“If you reverse it just to spite a judge because they’re not listening to you, where’s the justice to the victims?” Wasserman said. Then, he resorted to an analogy: “It’s kind of like saying I’m gonna take away your driver’s license because I don’t like the way you put your hand on the wheel.”

When asked if a better analogy might be taking the keys away from a family member with a drinking problem who had not killed anyone but ignored repeated warnings not to drive drunk, Wasserman thought for a moment and responded, “I suppose. I can see that somewhat.”

This content was originally published here.