Colorado’s inaugural independent congressional redistricting commission wrapped up its work Tuesday night and selected a final congressional map plan to use for the next decade.

The map still needs review and approval from the state supreme court, and it’s not yet clear that it will pass muster. At least two Hispanic advocacy organizations have said they plan to challenge the map as it heads for judicial review in the coming weeks, arguing that the map doesn’t meet the state constitution’s requirements to protect minority voting rights, despite efforts by the commission to group together Hispanic populations in the map.

The commissioners voted 11-1 to adopt the “Staff Plan 3 Coleman Amendment,” composed of a set of adjustments authored by Democratic commissioner Martha Coleman to the most recent “third staff plan,” drawn by the commission’s staff.

The map centers on two main mapping concepts that developed growing support among the commissioners in recent weeks.

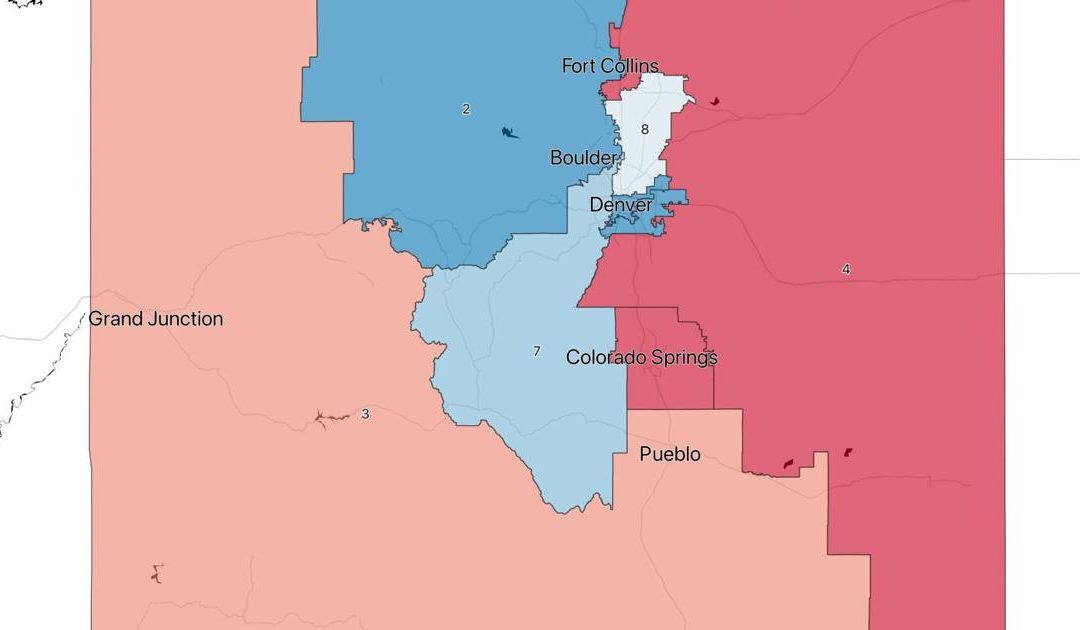

The plan creates a new and additional 8th Congressional District in the quickly growing and heavily Hispanic suburbs and municipalities north of Denver, and it creates a “southern district” that groups together the state’s rural Hispanic voters.

The Colorado independent redistricting commission adopted a final map late Tuesday, Sept. 28.

It has four solid Democratic seats, three solid Republican seats, and the new 8th Congressional District that falls within the range of what most consider to be competitive, but with a slight Democratic lean. In a swing election favoring Republicans, the tight partisan margin in the new district could lead to a 4-4 split congressional delegation.

The map also looks good for the state’s incumbent congressional delegation, with each of Colorado’s seven U.S. House members in a district that favors their party, but with no incumbent in the newly added 8th Congressional District. Earlier draft maps considered by the commission placed some of the incumbents into districts that wouldn’t favor their reelection, even though congressional candidates aren’t required to live in the district they represent. Notably, Republican Rep. Lauren Boebert was drawn into a Democratic-favoring district largely consisting of voters currently represented by Democrat Joe Neguse. But the two are both in safe districts in the final adopted map.

The final vote to adopt the plan came after four hours of debate and six rounds of ballot voting, all of which failed to meet the criteria required by the state constitution to adopt a final map: Support from eight of the 12 commissioners, including two of the four party-unaffiliated commissioners.

The commission is made up of four Republicans, four Democrats and four party-unaffiliated voters.

The Colorado independent redistricting commission adopted a final map late Tuesday, Sept. 28.

The single no vote on the final map came from Democratic commissioner Simon Tafoya.

By the end of the week, the commission’s staff will prepare the map and a report summarizing the entire process for submission to the Colorado Supreme Court. The state’s high court will review the plan to make sure it meets the constitutional requirements.

If the court approves it, the map will become the state’s congressional map for the next decade. The court could decide if the map doesn’t meet the state’s constitutional requirements and send it back to the commission for adjustments.

Two prominent Hispanic advocacy organizations have said the map fails because it will lead to minority voter dilution, specifically in the 3rd and 8th Congressional Districts, because the Hispanic populations in those districts, though they were rightly identified as voters who need to be grouped together, aren’t necessarily empowered to influence the outcomes of the elections in their districts. Both the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) and the Colorado Latino Leadership & Advocacy Organization (CLLARO) said Wednesday they plan to challenge the maps when they go to the state supreme court for review.

While the Hispanic advocacy organizations plan to directly challenge the plan, some of Colorado’s political class applauded the commission’s work, hailing the process as open and transparent, as others panned it because of the favor the districts give to incumbents or because the map didn’t go further one way or another with a partisan advantage.

Kent Thiry, the retired DaVita CEO, put his time, political capital and fundraising prowess into passing the ballot questions that created the two commissions in 2018. He was pleased with how they were working out on Wednesday afternoon.

“For the first time, Colorado’s voting maps were drawn independently, transparently and with meaningful input from the public,” he said. “After two redistricting cycles marked by partisan gamesmanship, it was inspiring to see 11 of the 12 commissioners throw their support behind a single map. Nothing is perfect, and there were strong disagreements along the way, but this was a dramatic improvement over a process previously controlled by politicians.”

The Colorado independent redistricting commission adopted a final map late Tuesday, Sept. 28.

Alan Philp, a Republican political operative and redistricting lobbyist who works for Colorado Neighborhood Coalition, a 501(c)4 nonprofit organization that doesn’t disclose its donors, similarly said the consensus reached by commissioners, along with the collaboration they showed, demonstrate that the ballot measures overwhelmingly passed by voters in 2018 succeeded.

“An 11-1 vote says it all. Amendment Y’s process demanded that people from different backgrounds, different parts of the state, and different parties worked together to adopt a map,” Philp said. “It was a process, but a process that worked. The Colorado Independent Congressional Commission passed a collaborative, consensus map that is fair, reflective of the constitutional criteria, and created a highly competitive, new Hispanic influence district.”

Curtis Hubbard, a Democratic political operative and redistricting lobbyist who works for Fair Lines Colorado, a 501(c)4 nonprofit organization that doesn’t disclose its donors, emphasized the public input that helped guide the maps, and the decision to put the new 8th Congressional District in the areas stretching north from Denver.

“In looking at this process that included submission of more than 5,000 public comments, consideration of more than 200 maps, and hundreds of hours of public discussion, there is much for Coloradans to be proud of,” Hubbard said. “The map must still go to the Supreme Court for final review, but the commission and staff deserve credit for working through a condensed schedule and agreeing on a plan that — notably — places a new, competitive district in the diverse, fast-growing area stretching from Adams County north to Greeley.”

David Pourshoushtari, the communications director for the Colorado Democratic Party, thanked the commissioners for their work, but chided them for some of the partisan outcomes of the map.

“We are thankful to the commission for its hard work on this map, but remain concerned that competitiveness came almost exclusively at the expense of Democrats,” Pourshoushtari said. “If the Supreme Court approves this plan, we are confident in our candidates and our ability to organize to ensure that Colorado will continue to move forward under Democratic leadership.”

Wellington Webb, the former mayor of Denver and the vice chair of the 2011 Reapportionment Committee, had harsh words for the way the new map provides an easy path for incumbents.

“I think, and from many I hear in the public, is they did the same thing that elected officials did: protect incumbents,” Webb said, comparing the old system to the new, with a laugh, after reviewing the map Wednesday.

“Look at who’s protected on the Republican side: Ken Buck, Boebert, Doug Lamborn. Those are safe Republican seats. They were before and they are after,” Webb said. “Who are the safe Democrats? DeGette, she’s been there since Noah’s Ark. Crow’s district actually got better, so the only one who got thrown under the bus was Perlmutter.”

Shawn Martini, the vice president of advocacy for the Colorado Farm Bureau, said rural communities on the Eastern Plains lost clout by getting mixed in with more populous urban areas on the Front Range. Less legislative focus on farmers and ranchers in Washington, D.C., would be bad for the economic health of a state where agricultural, tourism and energy are the main economic drivers, he said.

“We still don’t support splitting the Western Slope, regardless of where that split was made,” Martini said. “I think for rural Colorado, on the east and west side of the state, these maps mark a step backwards from what was in the preliminary maps. And other than that they’re pretty much even or they don’t really improve on the current congressional configuration that we have.”

He said the new map-making process could work, but it could do better than its maiden try.

“It was the first go-around,” he said. “It doesn’t necessarily mean that the process is flawed or it can’t be successful. It’s just that this commission didn’t do such a great job.”

This content was originally published here.